Life of an Amorous Woman

barely remember this, but it was good.

barely remember this, but it was good.the "amorous woman" (or what we scientific moderns would just call a n-mpho), finds herself degenerating further and further in society due to her insatiable lust. but, if I recall correctly, there were always moments of redemption.

since it was read years ago, I won't goodreads update it.

The Yiddish Policemen's Union

in the mad, slipstream flow of words that this 'review' will consist of, one might suppose the only animating concept or ideology is that of volume above all. "quantity has its own quality," said, apocryphally, Mao, leading to such military humor as "how many Chinese hordes came over the ridgeline today? A: three. I shot two, and the other guy ran away." the horde-like fascination of the East Asian swarm; the "hive mind," the group of indistinguishable individuals--I think I don't necessarily err in beginning the review in this way. I think, though, it isn't too much either to say simply

in the mad, slipstream flow of words that this 'review' will consist of, one might suppose the only animating concept or ideology is that of volume above all. "quantity has its own quality," said, apocryphally, Mao, leading to such military humor as "how many Chinese hordes came over the ridgeline today? A: three. I shot two, and the other guy ran away." the horde-like fascination of the East Asian swarm; the "hive mind," the group of indistinguishable individuals--I think I don't necessarily err in beginning the review in this way. I think, though, it isn't too much either to say simplySUBjECTIVE BOOK REVIEWING MANIFESTO.2014

Manifesto.2014 is sort of a proposal to ease out of the crisis of 2013. as everyone even half awake knows, a civil war erupted on GR last year, and although probably hostilities won't reach the same fever pitch of the chaotic flow of '13, of course there's going to be a simmering level of something or another this year. in fact (full disclosure: I am related by blood to Amazon legal, though I haven't spoken to her in years and she works on the mobile devices rather the social networks), sources indicate that even the conflict itself a topic of conflicting reports. does GR simply impose absolutist protocols on the reviewers and accept attrition as a fact of life? or does it side with even the Carpetbomber Air Bombardment Wing and open a new front in the timeless struggles of the publishing industry? I would tend to think situations like these call for a tangential response-- i.e., Amazon should hand out free gift cards to all the top reviewers while simultaneously maintaining patrol on auto-1/star accounts, but, you know, you don't necessarily get promoted for doing the obvious, and in any case, feelings might have hardened already too much in all camps... (but as they say, the consequences can't be known fully for now).

Manifesto.2014 is about the promotion of the Subjective Viewpoint. and by "Subjective Viewpoint," I meant exactly what is being demonstrated here, in this very text. that is, we've reached the third paragraph, but nothing has yet been written about the book. thus, we have the same exact situation as prevails between the celebrity reviewers and the Stop the Bullies Mafia: neither can exist without the other. nor can I, part of the Heartland Gentlehomme School of Being Nice to Writers notice anything except that a feedback cycle exists as well here, as 100% off-topic remarks lead ultimately to consumption only by the most fanatic of reader fanatics themselves. the relationship is also gendered, as there is a slight statistical preponderance of male writers and female readers. we exist, therefore, in karmic unity, never achieving, but never falling apart.

now in one concession to the karmic reader balance, I will note that 15% of my reading involves the UK and roughly 15% of my reading is written by or about the Japan. almost 10% of my reading involves Jewish culture, people, or the state. ~however~ Wikipedia reports that there some countless millions of Brits (more if you count 'Americans of at least part English, Welsh, Scottish ancestry'), and that Japan, too, totals some 110 million plus. according to WP, there are only some 20 million Jews in this world, although WP apparently can't calculate the full number of intermarried and assimilated and 'very small fraction of blood' Jews. in all though, statistics would seem to indicate a disproportionate output of writing, both fiction and non-fiction, by Jews, and so, without even planning it that ways, we have made one approach to the objective YIDDISH POLICEMAN'S UNION.

the obvious thing to do at this point, and what the objective reviewer would do, is to use this evident hook to delve deeper into the objective truth of the work. but wait, this is simultaneously a thesis about subjective reviews and an illustration of the same. if everyone agrees that even newspaper-standard objective reviews are two facts and then a long personal theory by the reviewer (and at least one highly regarded GR reviewer has this as their Dr. Strange and Mr. Norrell quote), then why simply aren't there more subjective reviews? and why is GR populated by so many fanatics, a larger group of big fans, and then that huge lurker crowd? I'm not sure I could provide an answer to this; nor am I sure that if I edited this piece to New Yorker quality erudition, that we would necessarily come closer to anything, anything at all. I'm relying more on a sense of deliberate impression or oblique commentary. I don't have to bring up the fact that I personally instructed a senior ADL director about early 50s Israeli history or that the fact that my parents were born in the 1930s and had me about as late as biologically possible makes me, technically, your parents' generation. these things exist, as do all matters, in a vacuum, unrelated, and unaffecting. finally, I should avoid the cheap humor of pointing out that the GR Anti-Defenestration League or "good guy reviewers" couldn't exist on their own either. We need the critical, acerbic, edgy, hostile critical critic. Goodreads needs you more than you need GR.

The proper, Subjectivist, analytical trope, now, is to talk, instead, about book acquisition circumstances. It's completely germane.

This is what happened. I had revisited the Shibuya Bookoff in search of Lethem's AMNESIA MOON (300 yen?), but in the space of 24 hours it disappeared and then I ended up with Scott Westerfield's UGLIES. Further investigation revealed much of nothing at all. There's a near paperthin J version of Iceberg Slim ("light novels" are huge in J writing these days). There's copies of THE ENGLISH PATIENT and John Ringo and Shusaku Endo's SILENCE. There's the prospect of finally cracking open Ian Rankin or Ian Banks. Here or there I might jump into a Cormac McArthy or a Tom Clancy or Grisham. But, pricing being what it is, 300 yen for YIDDISH POLICEMEN'S UNION lept out. 800 yen brand new, or $12 in many a bookstore (after markup). What a find.

What I already knew was that the work had won the Huge/Nebula although being alternative history rather than "Science Fiction." Classic mutual convergence of interests, as the Huge/Nebula sought slipstream grandeur and Harper Collins enjoyed more sales. The premise, a "Jewish autonomous state in Alaska, on the verge of reverting to US control" could have been other things.

* The work could have been about a small group of Jewish violinists, classical pianists, and ballet dancers, the last repository of European culture in a world submitting to super American crass and commercial dominance. Vaguely trying to assemble some sort of solution against reversion against a backdrop of fjords, glaciers, and arctic fog banks, ultimately everything listlessly dissolves into a nostalgia ridden evocation of old europe in the north.

* alternatively, the work could have followed a highly politicized and fanatic group of independence terrorists (/slash freedom fighters) who are slowly hunted down and whittled away by US security forces. playing off Doris Lessing's GOOD TERRORIST, the work could have ended either mutely tragically or ambiguously disastrously. with personalities such as "Joshua" the eye-glasses wearing intellectual, "Oren" the muscle man and machine gunner, "Miriam" the political strategist and financier, the small group dynamics would have played out against, again, all the fog and glaciers and mountains

* or finally, three, Chabon could have mashed up Richard Ford and Herzog rather than Raymond Chandler and Roman Polanski, so to speak. it might have been very interesting to see what Long Island and Manhasset would look like with an Alaskan Jewish Autonomous Zone rather than Alaska itself. from percodin-sniffing housewives to SAT-cramming teenagers, what aspect of Jewish American culture would seem familiar to our eyes and what entirely different?

in constructing these three alternative scenarios, I think I've pointed at least to some degree what YIDDISH POLICEMEN'S UNION was not. and so to that degree, I've held true to the Subjectivist Thesis. and it being 2014 and a new year, heck why not, start it off with a 5/5 and recommend for an experiment, a mash-up, and a riff. bearing similarities to MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN and all the other tips of the hat, and inspiring the ca. 2005 "my mother is a ukrainian tractor with everything illuminated" wave of similar Jewish identity / culture books, YPU succeeded in its statistical goals, and if a certain subtle Zionist undertone is also present, well that is the cost of entry, so to speak, to the author's private and now public world

Off-Topic: The Story of an Internet Revolt

The History of the Great Battle of 2013 has been writ....

The History of the Great Battle of 2013 has been writ....but as with every war, the full consequences will not be understood for years to come...

How to Be a Person: The Stranger's Guide to College, Sex, Intoxicants, Tacos, and Life Itself

Dan Savage, Lindy West, and the staff of the Stranger put out a quick book of advice about life, love, drugs, sex, rock and roll for 18 year olds. generally practical information (viz., pot won't kill you but DEFINITELY stay clear of heroin), and of course the Savage entries are pretty worldwide and amusing

Dan Savage, Lindy West, and the staff of the Stranger put out a quick book of advice about life, love, drugs, sex, rock and roll for 18 year olds. generally practical information (viz., pot won't kill you but DEFINITELY stay clear of heroin), and of course the Savage entries are pretty worldwide and amusingadded this in to counterbalance the 4s and 5s that have been filling up my reading queue. part of the situation is that Goodreads's glut of information now allows me to zero in, laserlike, on the very best titles. ordinarily that would be a good thing, but as one's average book rating creeps to 4 territory, suddenly there's an inversion of help-- if every book is a 4, then of course none of them are.

what else-- continuing economic chaos. as in, I gotta scramble for either China or Guam employment. 2 months of paychecks have dried up, leaving me working the Rolodex. 2013 is a curveball. thank god mere hours remain.

good reads cake day-- I approach or have passed the one year anniversary of joining GR. my primary contribution -- many of the top GR reviewers now peevishly note that "blog style reviewers" are annoying. yes we are . hahahaha

other developments-- goodreads formally transferred me from USA to Japan in its rankings. thus, I zoom from #117 reader in the USA to the #3 reviewer in Japan. haha, context is everything after all.

world scene: tensions, mildly rising?

Deep River

it's been reported in literary papers or sections that an unofficial "twenty-year rule" applies to the Nobel Prize in Literature-- that is, every twenty years or so (unless it was every twenty-five years, and I'm misremembering), the Nobel Literature Prize committee "has" to award the prize to a Japanese writer. such would not be unvelieable. if I remember the WP entry on the NPL correctly, the first twenty years of the prize were entirely Sweden or Sweden-Norway specific, until the realization slowly dawned that the entire world was watching what was then the only true international prize, and a large cash bonus to boot. Japan is 10% of the world economy and possibly that percentage of major world literature in sales, and perhaps more importantly to the publishing world at large, it highly respects copyright and will even invest in projects requiring half of all royalties be sent abroad.

it's been reported in literary papers or sections that an unofficial "twenty-year rule" applies to the Nobel Prize in Literature-- that is, every twenty years or so (unless it was every twenty-five years, and I'm misremembering), the Nobel Literature Prize committee "has" to award the prize to a Japanese writer. such would not be unvelieable. if I remember the WP entry on the NPL correctly, the first twenty years of the prize were entirely Sweden or Sweden-Norway specific, until the realization slowly dawned that the entire world was watching what was then the only true international prize, and a large cash bonus to boot. Japan is 10% of the world economy and possibly that percentage of major world literature in sales, and perhaps more importantly to the publishing world at large, it highly respects copyright and will even invest in projects requiring half of all royalties be sent abroad.the first big postwar duel apparently erupted between YASUNARI KAWABATA (the master of elegiac, short little pieces capturing Japanese uniqueness and intricate social minueting) and his protégée YUKIO MISHIMA (who wrote longer, more ambitious plot-filled novels about grief and longing). literary scholars, after decades of scholarship on both, probabliy feel the Prize was mis-awarded-- MISHIMA, despite his vainglorious death, is more highly referenced and influential; more writers fifty years on list him as "influence," whereas Kawabata, while known to the entire community, is more the origami-expert of the intricate fold.

today of course the central Nobel story is HARUKI MURAKAMI vs. HARUKI MURAKAMI. as in, will the Nobel Prize award the medal to HM or will it fail to act in time. no other name is seriously floated in contention.

the 1980s battle is interesting on a different level. both KENZABURO OE (the eventual winner) and ENDO SHUSAKU are a bit less read today and considered a step down from the KAWABATA-MISHIMA showdown. OE represented secular sociality and ENDO heretical Christianity. but aside from this issue, there is the overall sense of aesthetics in each's work, and of course the philosophy.

this is a book about five Japanese pilgrims to the Ganges and the "case" of each, describing the spiritual concerns and life events that bring them all to India for a brief trip. it begins "on the airplane" and then explores the background and history of each.

endo's other work I've read although a 3/5 non-fiction/fiction piece (literary analysis and just literature), always inspires rounds of conversation in artistic dinners.

this work is more just a very solid 5/5 lit work

The Comfort of Strangers

we are on goodreads, presumably, to meet disturbingly contrary opinions, so that degree, I'm chuffed (haha UK only word)... I'm chuffed that one of the publishing industry professionals here has put out a contrary take on Arthur Golden's MEMOIRS OF A GEISHA. I both understand and agree with this book's 800000 ratings status, to the degree that Japanese culture captures something universal, so we also understand that, for example ,Russians, Indians, and South Africans are all touched by this book. but it takes somebody who is embodying the contradictions of the industry itself to put out a "take down" of the work. anyway, investigate, o anonymous internet reader, for your edification, noting that even the Harry Potter works and Life of Pi, I think, are only at half a million ratings. (wish I could check further; this is mobile written).

we are on goodreads, presumably, to meet disturbingly contrary opinions, so that degree, I'm chuffed (haha UK only word)... I'm chuffed that one of the publishing industry professionals here has put out a contrary take on Arthur Golden's MEMOIRS OF A GEISHA. I both understand and agree with this book's 800000 ratings status, to the degree that Japanese culture captures something universal, so we also understand that, for example ,Russians, Indians, and South Africans are all touched by this book. but it takes somebody who is embodying the contradictions of the industry itself to put out a "take down" of the work. anyway, investigate, o anonymous internet reader, for your edification, noting that even the Harry Potter works and Life of Pi, I think, are only at half a million ratings. (wish I could check further; this is mobile written).mobile typing also means no hyperlinks. alas. when I had access to the land Internet, I do recall fondly following (and creating) links, picture. but text only perhaps contains its own opportunities for engagement. formal book reviews, of course, tend to be hyperlinkless. there's tradeoffs everywhere. final note (and last time to mention it, I do affirm this), mobile goodreads site means no "space remaining / character remaining" notification at the bottom. it's liberating from the necessity to try to "challenge write" a full, maximum-permissible sized review.

okay, now the book.

what to say. an analysis of this work has to begin with the fact that I'm in atonement for ATONEMENT. wah, couldn't resist that. what I'm getting at is that I rated ATONEMENT 3/5 in response to the buzz and the breathless praise about it. too many people, too many sales. bestseller status. the end result is that I thought the story narratologically weak, and lush visuals do not compensate. I didn't like the twist. but, rating Ian McEwan's master piece / magnum opus at the uncomplimentary 3 now instills some obligation for a more liberal treatment of his back catalog. well, yesterday or the day before I put the 4.2 or 4.4 SWEET TOOTH at the 5. but I'm still riding that guilt roller coaster. so here, too, maybe this 4.6 gets the full 5.

COMFORT OF STRANGERS is McEwan's Venice novel. there's a Venice expert here on GR, but even generalist readers kno that Mann, Waugh, and Forster all did a Venice novel. can a late 20th century writer DARE to put out a Venice book considering the weight of those names? call this point one (1) why McEwan gets a plus.

second, this second McEwan book succeeds in his trademark structure and re-read strengths. you can't go through it once; you have to see it at least twice. early sections riffing off Bowles' SHELTERING SKY and influences from John Fowles noted. conclusion: COMFORT OF STRANGERS is a sort of meditation on cool Nordic, Protestant gender-relatioships versus hot-blooded, Catholic, mediterranean sensuality. it is curiously tangential to the WP entry, which is perhaps a commentary on the literariness of Wikipedia editors. one of the first McEwan books where I found myself finding true divergences from the WP entry, which, at least, is spoiler free. (one must give it that much). the work, as any WP reader will note, is about two couples, but I think McEwan's later output confirms that one of his preoccupations is rational Englishness versus the alternatives. you might not like either couple, but one or the other will seem more familiar.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The Comfort of Strangers

the WP entry does a lot. this is my sixth McEwan so he is the surprise hit of winter 2013 for me, and though presumably at this point, half-a-dozen books, I'm allowed a certain further tone of authoritativeness in these reviews, I guess I can mostly just say that this does have a shot at being his bst, it is limited in location to Venice over a couple weeks or less, it explores issues similar john Fowles's exploration of gender relationships, and it passes a large amount of commentary on the modern Beta male known to US and UK citizens and the "Mediterreanean temperatment." McEwan manages to not just vocalize, but preserve in literary form for posterity a culture shock, a culture difference that millions have surely noticed. the ending, of course, is the entire work.

SWEET TOOTH

Merry Christmas, Goodreads. With holiday carols filling the aisles of shops around the globe, I thought I would attempt that difficult but not quite impossible task of "maxing out" the Goodreads review--that is, reaching the character limit on a book review, and making, scout's honor, at most 10% bloggish commentary about the reviewer's current circumstances. Given this set of parameters, it would only seem the practical way of limiting the review's content to 10% blog-style notes is to begin with them, so there goes the first paragraph.

Merry Christmas, Goodreads. With holiday carols filling the aisles of shops around the globe, I thought I would attempt that difficult but not quite impossible task of "maxing out" the Goodreads review--that is, reaching the character limit on a book review, and making, scout's honor, at most 10% bloggish commentary about the reviewer's current circumstances. Given this set of parameters, it would only seem the practical way of limiting the review's content to 10% blog-style notes is to begin with them, so there goes the first paragraph.The bloggishness goes something like this. Japan itself is a country for narcissists because it, upon having a few encounters with the outside world in the 16th century, decided "the problem with foreigners is that they exist." Correspondingly, it secluded itself on pain of death (death penalty to all landing foreigners; death penalty to any Japanese who dared leave and then return) in the year 1600 and remained behind closed ramparts until, famously, the 1840s arrival of Admiral Peary, United States Navy, with all the scholastic commentary on that clash of civilizations that followed. To that degree, if you are a reviewer, you are also a writer of sorts, and if you are a writer, you are composing in your head at times, you are seeing events at a remove, you are mentally comparing things you have read to the stimuli reaching your consciousness through the senses. Combine the authorial/reviewer temperament with "being in Japan," and reviewer therefore deserves some leeway for all this obsessive documenting of circumstances. Or maybe not. But who else to capture the rose color of the skies on an early winter afternoon, the frivolous swish of a maid-costume-wearing twenty year old, or the way sunbeams glitter off a unpolluted stream? I don't know. I can't invent excuses for things as they may be.

If this isn't enough justification for an entry point to a review, there is other matter of Ian McEwan circumstances. Imagine: 2007. You're in New York after a first stint in Japan. Many university classmates are still around the city, enlivening things with information about where to go and who to be. The sunlight glitters softly through Central Park trees, and buses are paneled on the side with ATONEMENT advertisements. On the Internets, quick video shows glittering soft-focus imagery of 1920s England, the Brideshead Revisited thing, the Anthony Powell thing, the Lost World thing. This was civilization, is the unstated message; what we have now is the residual aftermath. Yes, say the rotund matrons of the Upper East Side; yes, proclaim even the bespectacled intellectuals of Morningside Heights. For once, a few brief hours in a darkened cinema, we will relive England in her glory.

It worked for a lot of people. I bought into the advertising campaign too much, and felt the story let me down. The novel may have been icing on that cake. The review / opinion still stands today; my take is that Atonement promised much (although perhaps it was mostly the Hollywood hype); the McEwan "twist" in this case was a cruel stab. More generally, I felt the plot's failure to deliver was that it failed to enter the minds of the 20s-decade aristocracy. Powell could do, and so could Waugh. Even Oscar Wilde seems to be offering a sort of entree. Isn't McEwan cheating?

Based on this disappointment, I did not pick up another McEwan for a couple of years, and this was On Chesil Beach, which I similarly thought on an initial run through was "aching to break through," but failed. My judgment on Ian McEwan: an author of the "storm in the teacup." He could not move mountains and continents in the way even of Nabokov's short fiction could; he came short even of Ishiguro in his scope, sweep, grandeur, and ambition of his work.

Enter Goodreads. Based on statistical feedback from the entries I picked up Saturday, and then reread Chesil Beach. I found Enduring Love, and the Innocent. Executive summary: Atonement (3/5 based reaction to the quarter-million audience and raves, actually a 4/5 technical achievement), Saturday (3/5 solid, disappointing, all about Dr. Perfect), but then Enduring Love (4/5 pushing the 5) and Innocent (4/5 high). Finally McEwan has gotten some traction. The thing is falling together.

Since I downplayed Atonement for reaction reasons, I have to push this 4.6 work up to the 5 even. The motivation is to balance out the five novels, 3.8 being a fairer number of the output looked at thus far, and perhaps capturing some of the feeling of wanting to see the rest of the catalogue. Finally, before proceeding the analysis / reviewing of the book content, there's the issue of McEwan entering his sixties. We may not have him for decades to come! Let's build the excitement around his work while he can still appreciate all the online accolades.

SWEET TOOTH

as Multiple online reviews have already noted, Sweet Tooth is about a young female recruited into MI-5, Britain's internal security service, and invited to participate in the least violent, most cultural activity. Since I am not a newspaper reviewer, I will go one step further in discretion and keep out details from this entry, although any google search on the Independent or the Boston Globe will provide details about the first quarter of the book.

The real skill, of course, is to talk about things in all generalities. Well, first of all, one more digression, how did we get here, 2012, Ian McEwan knowing he is starting to reach the danger point at which hearts suddenly stop or falls end a career. We have:

Atonement: the huge, huge crowd pleasier, estimated 1.5 million copies sold worldwide, a brilliant and warm evocation of 1920s England and a huge literary trick that showed the vitality of the modern novel to confound and disorientate. also, however, a trick in a way, a storm in a teacup, and less daring in scope than Waugh or Oscar Wilde.

Chesil Beach: a work for a certain subset. Two newlyweds on their honeymoon on the shingle in the south of England. MCEwan argues for a certain traditional way of viewing things, in contrast to 60s values. A celebrataion, in a way, of a lost type. Underyling ethos conservative.

Saturday: true celebration, true glorification of upper-middle class professional London counterposed against the twin suggested destructive forces of terror and crime. A reminder that liberal social values can also just meet medical diagnosis. Celebratory about Dr. Perfect, and one kind of London smart set.

The Innocent: early MCEwan, not very read. Moment by moment dissection of an extremely, extremely innocent young man who gets inexorably caught up in love and espionage. Berlin during the Cold War, and a riff on an actual event involving the Cambridge Five (Soviet moles in SIS).

Enduring Love: acid dissection (in my reading) of "hard" theism versus tolerant, non-evangelical secularism or progressive theism. Dr. M, physicist and #1 reviewer on UK Goodreads, disagrees, but in any case, we can agree this work is an endorsement of rationality and modernism vs. aggressive radical and external forces.

Well, so here we go. Amazing in a way that a writer, somebody in any case part of a tiny, not hugely loved minority, endorses the Establishment, but therein, perhaps, lies a clue to this work, wherein McEwan clearly hints that aspects of the work apply to him. Was a writer in the book given the (fictional) "Jane Austen Prize for Fiction?" Well, McEwan, it seems, won the Somerset Maugham Award early in his career--and Maugham, of course, after writing the first blockbuster thriller in history (and becoming rich), spent his later life in service abroad in China. So, wink-wink, McEwan is hinting--wink-wink--that he has in fact accepted mild forms of government support for his work, and so we have a clue to understanding the McEwan enigma. McEwan is--at least partly--at one with his government's values, and if he doesn't absolutely declare that he has received discreet support, well at least we can understand that doors are open to him, and he is welcome at many a table. But then, of course, doors were open for Doris Lessing, and she was also welcome, and she was at least for periods of her life a declared Communist. Wah, what a complex world.

This interplay of authors life and novel's plot is just one part of this book. The work also exists as a demonstration of literary craft and twist; it evokes internal universes (in one of the quoted passages, the heroine describes her feelings at being present at a counter-culture event while salaried for MI5); it explores ironies of both leftist cannabis smokers and right-leaning writers being on government dole. But aside from all these issues, Sweet Tooth is about a certain type of girl--easily led by her parents to study what isn't her desired subject, but of sound mind and definite opinion. Conversation about literature serves as both vehicle for discussion and dissection of the postwar novel (McEwan isn't personally criticizing certain word-game players and authorial-present authors, but his sympathies resound because of course his own work is consistent with one of the viewpoints), and the philosophy of art as present does correlate with certain passages elsewhere in McEwan's writing. His work speaks for itself, and is itself commenting on itself, and the difference between the two is precisely part of the thrill.

I would hold, so to speak, that this presentation of the novel so far is doing a fair job of presenting what the crux of the book is without actually revealing the slightest of spoiler details. But of course this interpretation fails to cover, for example, the 70% of the book that isn't, per se, about McEwan. we have certain value points here for why this book deserves the 5, even if it's preacknowledged to be a 5 that's counterweighing the 3 I currently (and will for the future maintain) for ATONEMENT.

> value proposition 1: SWEET TOOTH provides the equivalent of 30 pages or so of literary analysis as vehicled through the narrator, a Bishop's daughter, who becomes increasingly drawn to literature as her Maths proves less than Cambridge Tripos quality. then, in a later section, the narrator meets the McEwan avatar, and another literary school of thought develops. all in all, most of 20th cent. college lit and pomo lit is critiqued.

> value proposition 2: the Anglophile Angle. as with the rest of McEwan, what you're buying is a few hours' vacation in the UK without the inconvenience of air travel or the expense. McEwan is far and away, the most local and globalized writer of upper-mid UK; hence, "we motor along the M40 until reaching Telford, whereupon turning off onto a dirt track we find Colonel Kiers' cottage, and leave the car to find the Colonel with his Springfield, hailing us from some thirty metres..."-- you know, there is at least some segment which is buying McEwan for this sort of thing, as well as entree into a not entirely open society

> value prop 3: McEwan's own take on life and the world is only further developed and revealed in this work; together especially with ENDURING LOVE, but also with CHESIL BEACH and the INNOCENT, we develop a word-picture of values and secularism.

now, as it happens, mobile Goodreads does not list a character limit, (ipad IOS). therefore, my little project is nipped in the bud. i know I'm far short of the actual review size limit, but unless I have a real idea, I can't spaz out in writing if there's a risk thwo thirds of if it will disappear. I guess I will say, these are the key points:

STRUCTURE a McEwan strong point, book can 't be read just once, as with his other works

"This is England," McEwan both expressing and of his own nature demonstrating English values. anglo-saxon secularity implied to be the last hope of man

possible interfaces: some fo this is drawn from open source sources, and McEwan has had the plagiarism charge leveled at him. he devotes a chapter to the Monty Hall problem. he ties together various things (see above-- regarding structure and teacup) but his best moments are when you're not sure what is actually autobiography, what is extremely skillful mind reading of a different gender narrator/person; and what is pure fabrication. the work is realistic/naturalistic and believable, and yet, and yet, it remains part of the "tea cup" problem. isn't McEwan completely missing the most interesting story of all, why the British security forces (and the US, as well), constantly end up on the same side of global politics as al-Qaeda? don't you turn on the news every saturday and learn that, in the most central of ironies, al Q and the US counter terrorist forces ARE BOTH IN AGREEMENT that Qaddafi, Hussein, and Assad should all have been or should be overthrown? why doesn't McEwan explore this strange coincidence / undeclared alliance / whatever it is? what is going on? why is this universe so random?

Uglies (Uglies Trilogy, Book 1)

I. bloggish rambling,

I. bloggish rambling, II. book acquisition details for the penniless,

III. the actual work as a stand-alone creation,

IV. notes on the book's reception/place in the totality

I. shibuya blue

some people don't mind the bloggish notes on what the reviewer is up to; others prefer to skip ahead to actual "Literature Discussion." for whatever posterity's sake or curiosity's sake, I rode a bike into Shibuya for the first time in my life, making it roughly 15 years since I first wandered down Center-Gai, wide-eyed and almost disbelieving. what can you say. it's Disneyland on speed. it's Fashion Capital. it's that unique entity called Japan and one of its most unique 300 meters. all the tourists standing around with cameras out point to something going on, although what exactly it is might not be absolutely simple to characterize. knowing anyway, that bloggish notes are downplayed on our beloved GR site, I guess I'll have to summarize this section just as, is it better to be making $3 thou/month at some desk job in the States or *literally watching every yen* at 900 USD/month but biking into Shibuya? what a mystery!

in any case, contrary to the situation this summer when I had a library and infinite time, it's now work 30 hours/week, and a mind a bit too tired to do anything but strum through children's literature. hmmm... wanna get my hands on the final third book of the Ramona Quimby "dark period". such mindless fun, what a delight!

II. book acquisition

the book was acquired accidentally, at the Shibuya Center-Gai BOOKOFF. hmm. the previous day I had noted Jonathan Lethem's AMNESIA MOON for 200 yen. the city moves quick! the very next day AMNESIA MOON was gone, and the next best opportunities at the 200 or 300 yen level were a variety of vaguely literary titles. as it were, though, I think one was a LeCarre I had already read, another a mere airport paperback thriller. Scott Westerfield UGLIES, although 300 full yen, at least had the endorsement of some untold six figures on GR (as I remembered it; I have to type this out on Bluetooth keyboard and then copy-paste; the actual number is fairly easily accessible on the GR entry. in any case, it was one of those 'huge' numbers. hundreds of thousands of teenagers can't be wrong).

III. the book!

probably immediately after uploading this text, I'll be able to check out what all the GR crew has said. if you're new to the website, look up Penketron, look up Dr. M, look up Ceridwen and *the professional*. haha, names altered for fun's sake. anyway between the newbies on the site and the long timers over by the fireplace, everyone seems to be having fun with Facebook for booknerds. hahahaha. is there some crisis going on with reviewer censorship? you should see Red China. neighborhood watch officers on every street corner and a thug-like paramilitary force that beats up market stall owners. internet auto-purge and auto-block that operates on a "warning system;" i.e., lookup Tiannanmen Square two or three times, fine, no page delivered; look for it the fourth time and the internet for you goes down for a couple minutes. this isn't a joke!

anyway the book is good. 4/5. I resisted looking up Wiki-details on the work until completion, and was pleasantly surprised to discover that no, Westerfield did not plagarize HUNGER GAMES. this book came out in 2005, and HUNGER GAMES is 2009. but there were some similarities, as there were also to SHIPBREAKER by Bacigalupa (YA dystopian work by winner of Hugo/Nebula for WINDUP GIRL, a 5/5 masterpiece). is it just the genre? or are quick-thinking teenagers always in imminent peril, fighting against a corrupt government that doesn't simply eradicate them. hmm. had I been running District 1 in the Hunger Games, I would simply have gassed Katniss at any opportunity I had of sending rose-floral essence her way. *PLOT HOLE* hahahah. but although this genre must always been composed of various flights, chases, moral conundrums, and sheer "world showing" (=as in, your imagination creates an entire corrupt world, and then plot seems to be bent in order to take the heroes/protagonists on a guided tour of that universe), the flaws that can be pointed out (slightly weak plot sequence at one point in the Smokies setting, character noticeably less complex than 2009 Katniss Everdean), at the same time, "crowd-pleasing work" I guess has to appeal to a certain lower common denominator. an attempt at adult literary fiction calls for both acid and absolute precise delineation of emotion and political commentary; this YA stuff has to paint in broad-strokes, this I think, we just have to forgive the artist.

compared to Leviathan, a somewhat more believable fictional universe (Leviathan gets some technology stuff just wrong), comprising, as mentioned, the hero teenagers struggling against near-future dystopia. a possible parable-reading has been noted by at least one eminent critic (= novel as metaphor for maturation? acceptance of conventional values?), but otherwise a degree of cotton candy teeny bop "teen anxst" combined with HG action, MTV-generation societal understanding, and dialogue- and action-strong crafting. forced to choose between this book and Hunger Games in the "burning library scenario," I'd take Hunger Games, but clearly this 4/5 is worth a read and flows.

as far the much-beaten-to-death subgenre of teenage dystopian action YA goes, this is definitely still worthy of adult interest, and if it times it seems just a BBC made-for-TV movie with its rapid plot, at the same time, it has some usage for work-tired minds on a lazy sunday. I think I will not be putting down the $9 for the remaining three volumes, which leaves BOOKOFF with volumes 2, 3, and 4 of the series, but hey, capitalism goes both ways.

finally, for those remaining precisely on the fence on whether to get this book or not, suffice to say, "it's YA chase sequences and action taking place across a possibly-oppressive high tech city and then the wilderness that shelters the Smokie resistance. quick-moving without huge amounts of intellectual commitment, along with some crowd-pleaser social commentary on physical beauty"

Ramona and Her Mother (Ramona Quimby)

Goodreads.com's perhaps most respected reviewer, Dr. M of the department of theoretical physics and Pooh-studies, has perhaps written his most eloquent entry on the 1965 science fiction blockbuster, DUNE. M relates how it is the world, rather than the book, which has changed, such that if written today, the book would seem to be an endorsement of radical Islamic politicism, led by a charismatic leader, whereas at the time--and therefore now inaccessible to the younger reader, was the fact that the book was a sort of distillation of American Romanticism about the Arab world. There was once an America that rooted for the sand-dune dwelling nomads! Once Islamic revolt was an appealing possibility!

Goodreads.com's perhaps most respected reviewer, Dr. M of the department of theoretical physics and Pooh-studies, has perhaps written his most eloquent entry on the 1965 science fiction blockbuster, DUNE. M relates how it is the world, rather than the book, which has changed, such that if written today, the book would seem to be an endorsement of radical Islamic politicism, led by a charismatic leader, whereas at the time--and therefore now inaccessible to the younger reader, was the fact that the book was a sort of distillation of American Romanticism about the Arab world. There was once an America that rooted for the sand-dune dwelling nomads! Once Islamic revolt was an appealing possibility!in my own central focus, military writing, a similar but not exactly corresponding phenomenon exists. the US BLACKHAWK DOWN and the UK BRAVE TWO ZERO are two works that are quintessentially 90s. in the 90s, special operations consisting of noble, highly-trained professionals at war against the environment, the mob of humanity, the ruthless seemed to be the tone of the future. then came 9/11. instantly these books were relegated to the back shelf of war non-fiction, as once again the idea of country vs. country, national invasion vs. national army, republic vs. republic became the seeming tone of the 2000s. even today in 2013 the possibility of an armed incursion into a secular republic does not seem incomprehensible. the idea of a small forces hostage-rescue mission or special forces decapitation mission would be less fascinating, less studied. Ancient Greek Philosophhers might warn us that therefore such an incident is all the more likely, but who knows, who can say...

well how does this relate to RAMONA AND HER MOTHER. well, possibly Democritius aside or the Heraclitus or whoever that proto-Stoic was, we're going to understand this work in reference to the fact that the reviewer is abroad, looking at Americana, or overworked and absurdist, who knows. or no, actually, the important thing is that Israelis and Arabs went like this:

1948 Arabs try to destroy Israel

1956 Israelis try to punish Egypt

1967 Israelis preemptively strike United Arabs

1973 Arabs suddenly shock Israel in the October War

now whether you believe the US airlift to Israel was a massive and material change in a regional "fairly fought" surprise war, or whether the notion of a world without Israel is something that makes your blood boil and causes you to consider enlistment in the IDF, the Arab reaction of the "oil embargo" was either (a) a fascinating case of life imitating art (Dune was published in 1965 and discussed 'spice embargo', or (b) the important predecessor reason for why the US economy fell into recession in 1974, why the 1976 Bicentennial celebrations were therefore a bit subdued, and MOST IMPORTANTLY, the cause of Beverly Cleary's "dark period" of Ramona 4 and 5.

the Quimbys are hit by a recession! this squeaky clean 50s family explores family strife and economic reversal! but the depression or loss suffered by the artist is ultimately the gain of the reader, for whom these two children's books remain readable, even in one's later years. yes, I guess, ultimately, Ramona 4 and 5 probably just about equal the rest of Cleary's output. it's tough. Ralph the motorcycle-riding mouse is also entertaining. but... then again, wouldn't I rather have Charlotte's Web and Stuart Little and Trumpet of the Swan than all of George Selden's output? hmm. tough questions. the famous "burning Louvre" problem seems to bring up conundrums as well even for kids' lit.

complicated, ,twisted individuals, I guess, are just better. hmmm wasn't there some female CEO who supported one obscure brand of German opera. maybe a more valued addition to the gang we call humanity than a thousand apple-pie baking moms.

Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman: Twenty-four Stories

Tokyo, Sunday 3 November 2013, 1944 local time

Tokyo, Sunday 3 November 2013, 1944 local timeI'll borrow a page from the Penketron playbook, and put out a longish entry on a short and sweet book. but wait, BLIND WILLOW, SLEEPING WOMAN isn't actually a short book. it's twenty four short stories by that master of hyper-contemporary Japanese literature, Haruki Murakami, some 360+ printed pages of text or presumably in excess of 70,000 words+. so why does the adjective phrase "short and sweet" apply so easily to HM's output? possibly for the same exact reason that Murakami was resisted by the famous "Japanese literary establishment" in his first decade of writing 1979-1989, for his neo-contemporary, sweet without seeming substance, word-play without historical sweep, even 'superficial without profundity' surrealism and confection-like style. love or hate, though, Murakami remains the touchstone of 1990s-2010s Japanese letters, and if he lands the Nobel or if he doesn't he is still the number one name to discuss before you turn to talk of other J-greats, Ryu Murakami, Miyuki Miyabe, Natsuo Kirino, et al. do you like the neon-swept high-definition television screen lit up weekend paradises of Shibuya, Shinjuku and Roppongi? or is Japan to you its forgotten islands and wind-swept valleys deep in forgotten seaside prefectures? is your taste in dessert honey-dripping cinnamon apple goodness or do you think coffee should be black and bitter?

in a twist worthy of the surreal style of HM himself, a short work like this conversely inspired far more examination than a 1000 page tome on WW1. what can a reviewer say about an academic work filled with accurate statistics and day-by-day coverage of the micro-changes on the Western Front, when after all the 24 stories of BWSW offer a dozen possibilities or more of critical reading?

for example, just starting, I might point out

* Birthday Girl's double inclusion in this and After Dark (?) to inspire separate effects in each collection

* 'How He talked to Himself as if Reciting Poetry's' intertextual reference to Raymond Carver's most storied story

* Hunting Knife and hidden revelation about J feelings on the US

* 'A Perfect Day' being Salinger redux

* Nausea 1979 on a friend who might be the nauseating

* Sharpie Cakes' allegory being revealed in the preface

* ice Man's verbal similarity to 'Gaijin'

* Crabs and the Sinic English speakers?

etc. etc. etc.

Rather than dwelling on each piece, or rather, before dwelling on each piece, I guess the most intelligent thing to point out is that, possibly in the year 2050, some scientific/CS/IT analytical solution of human minds will point out that the fact that a CD album and a novel or short story collection are not coincidentally about 2 MB or data each (up to 4, depending on resolution). in other words, a year's output as a single, discreet artistic object are in some bizarre coincidence, almost exactly the same amount of binary data. well, most pop music is actually a collaborative output, but then, so to speak, writers exist in a unseen team of agents, publishers, marketers,, and critics. do were merely conclude that 2 - 4 MB of data is just enough coverage to examine in whole, race, sexuality, culture, and philosophy? and if so, does BWSW cover all those bases, in particularly with reference to Takitani, Hanalei Bay, Dabchick, and NY Mining Disaster? and is the last a dream dreamt of by asphyxiating miners or are the miners dreamt of by the modern Tokyo twenty-somethings?

I think any Haruki Murakami work has to include the simple fact that surrealism and strange imagery, strange juxtaposition does of course carry its own charm and possibly even its own message. perversely, the more Murakami seems to in this work communicate nausea or uneasiness about the foreign, the more spectacularly well-liked his work is by the foreign audience. one of the things about HM, of course, is that he is actually a pro-foreign writer in a way Mishima certainly was not, and that probably Kawabata will never be thought of as. even Soseki's outside country characters don't seem spectacularly front and center, this is possibly the challenge of J-lit and it's source of appeal. what is meant to be said is that simply exclusion is its own justification.

in any case, this review is probably reaching its justifiable length regardless of prior attitude or commitment. if you are unsure whether to commit to the time and effort of this work, do HANALEI BAY, do the title piece, and maybe TONY TAKITANI, and if none of the three strike a chord, probably the collection as a whole will be a loss. however, if you are a Murakami fanatic and Norwegian Wood seems written "just for you," of course plenty of discussion inspired ascertaining exactly whether Murakami is a limousine liberal of the upper-middle class, a channeler of the sentiments that exist in the Friday night kitchens of Aoyama, or whether his work is going to spectacularly endure for three centuries as the first J-writer to escape the weight of pre-war Japanese tradition.

in any case, this is perhaps the classical Murakami short story collection. surrealism meets actual narration, and exceeds AFTER DARK in its sweep of the human life, history both personal and national, as well as possibly the most elegant case study of juxtaposition ever written, NY MINING DISASTER.

Ramona and Her Father

there is darkness even within the lightest works, and light sparks here and there is the ultimate downer novels. WP says that Cleary was advised to write peppy and light and humorous, but scholarship on children's literature, as such exists, actually takes formal note of the 1977 "dark period" where light and peppy children's book writer Beverly Cleary first saw the intrusion of darker themes in what was up to then the all sunshine Ramona series. the incorrigible Ramona, of course, is the somewhat spoiled and spunky hero of several books that remained purely in prepubescent timeframes, but at least according to one source was intended at one point to start flying into the swirl of young womanhood. did the world miss out a masterpiece? or should childhood nostalgia pieces remain forever unsullied by the vortex forces of adult life? does it make sense to rate a child's book on GR and then have heaps of unwanted comments flowing across your log-in page? do I complain too much about this issue?

there is darkness even within the lightest works, and light sparks here and there is the ultimate downer novels. WP says that Cleary was advised to write peppy and light and humorous, but scholarship on children's literature, as such exists, actually takes formal note of the 1977 "dark period" where light and peppy children's book writer Beverly Cleary first saw the intrusion of darker themes in what was up to then the all sunshine Ramona series. the incorrigible Ramona, of course, is the somewhat spoiled and spunky hero of several books that remained purely in prepubescent timeframes, but at least according to one source was intended at one point to start flying into the swirl of young womanhood. did the world miss out a masterpiece? or should childhood nostalgia pieces remain forever unsullied by the vortex forces of adult life? does it make sense to rate a child's book on GR and then have heaps of unwanted comments flowing across your log-in page? do I complain too much about this issue?well... who knows. for me, GR is and cannot be a popularity contest. in fact, trick's on you, the unwitting reader of my microblogging, since I'm using this venue to vent about the frustrations of daily life. as in, (1) did you know that many Japanese somewhat resent the outcome of WW2, (2) isn't it manifestly unfair that a company/employer can just declare policies but an employee just has to put up, or (3) if you buy something with counterfeit cash you can go to jail but if a product fails on you, you have to take extraordinary measures to get a replacement. see, life is stacked against the individual!

anyway, this quasi-manifesto-cum-book review I suppose leads to the interesting question, "what about that debt limit everyone?" I have this burning question for economists--if the US gov't can just print as many bills as it pleases, doesn't it mean that the foreign debt is just a construction? if I borrow cash, I have to come up with cash to repay it plus accumulated interest. but governments control the currency, and therefore can't technically become bankrupt. I don't get it! somebody with economics studies under their belt explain this paradox.

right, right, the book.

well, like, Ramona's parents still love her, and nobody seems to mind being lower-middle class, and the family can scrape by on a single earner's wages (at least temporarily), and the nuclear family is still intact. this is 1977, with a 1950s outlook, more or less. since then the American Family has sort of broken down into methamphetamine, payday loans, and street hustles. so, of course, vote democrat, support social reform, seek student debt easement.

The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World Before the War, 1890-1914

I've been punching out the four stars lately, but in justification, if the book is a two I usually just let it gather some dust. Even the threes take longer to finish and then I usually find some excuse to delay the write up. Fours I can consume like potato chips.... Munch munch munch. Supposedly reading is good for you, but after three hundred books this year, non fiction even, I know even less and less.

I've been punching out the four stars lately, but in justification, if the book is a two I usually just let it gather some dust. Even the threes take longer to finish and then I usually find some excuse to delay the write up. Fours I can consume like potato chips.... Munch munch munch. Supposedly reading is good for you, but after three hundred books this year, non fiction even, I know even less and less. Tuchman is famous for "guns of august" which probably established the concept of the popular history work. Putting style above research, the result is accessible rather than groundbreaking. Here in Proud Tower Tuchman buys into the idea of "Germans as bullies", but otherwise accurately portrays the myth of the belle époque. I write "myth" because of course the world in 1890-1914 was composed of millions of unprotected workers, rather than the two hundred people at Le jardin de Luxembourg . Still there is the sense that great catastrophe awaits as well as efforts to avert the crisis.

To some degree, this work is marred by an over-emphasis on Tuchman's specific concerns. Suffragism gets extensive treatment, as does an acid dissection of France's handling of the Dreyfus affair, but the world shaking victory of Japan over Russia in 1905, less than twenty years after feudal Japan was opened to the West by Peary, sees little mention. Further, other historians have done better coverage of the incipient decline of the great English aristocracy, and Dadism seems less examined than it might have been, also Tuchman does cover some aspects.

Overall, a fine essay and examination of a world on the brink.

2

2

In Pharaoh's Army: Memories of the Lost War

The Vietnam War memoir has been harder than expected to find. tim o'brien is probably the famous name of the genre, but as it turns out, he is writing fictionalizations. Guns Up! is strong and full-throated in its one way. Enter Tobias Wolff. At first echoing will manchester's (ww2 vet) seemingly distant /dissociated/ even perverse confrontation with the absurdities and hollowness of war, Wolff quickly gets involved in a slightly mournful but at times mordant dissection of military realities. He is no gung-ho hero but neither is he a superior-complex ridden officer. The actual content of some anecdotes is not always jaw-dropping ( one whole story is just about hovels being blown away by rotor downwash) but there is recognition of Vietnamese realities and rule-bending and risk-taking.

The Vietnam War memoir has been harder than expected to find. tim o'brien is probably the famous name of the genre, but as it turns out, he is writing fictionalizations. Guns Up! is strong and full-throated in its one way. Enter Tobias Wolff. At first echoing will manchester's (ww2 vet) seemingly distant /dissociated/ even perverse confrontation with the absurdities and hollowness of war, Wolff quickly gets involved in a slightly mournful but at times mordant dissection of military realities. He is no gung-ho hero but neither is he a superior-complex ridden officer. The actual content of some anecdotes is not always jaw-dropping ( one whole story is just about hovels being blown away by rotor downwash) but there is recognition of Vietnamese realities and rule-bending and risk-taking.Part of the use of war books is that it helps us deal with civilian life frustrations. I got sort of railroaded into $4 or $5 over expenditure at a Tokyo Internet cafe yesterday but if you compare that to being mortared, clearly things fall into better perspective.

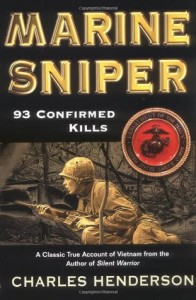

Marine Sniper: 93 Confirmed Kills

having been fairly generous with the 4-stars lately, I guess I have to lean towards the 3 on this 3/4 borderline work. there are distinct arguments for the 4-- the ending, the multi-functional aspects of Henderson's capabilities, some of the uniquely defined personalities. but there are also areas to question, most famously (apparently, for Henderson addresses the issue in his foreward), a scene where people talk, and then one disappears into the bush and the other dies-- how could Henderson reconstitute the conversation?

having been fairly generous with the 4-stars lately, I guess I have to lean towards the 3 on this 3/4 borderline work. there are distinct arguments for the 4-- the ending, the multi-functional aspects of Henderson's capabilities, some of the uniquely defined personalities. but there are also areas to question, most famously (apparently, for Henderson addresses the issue in his foreward), a scene where people talk, and then one disappears into the bush and the other dies-- how could Henderson reconstitute the conversation?Henderson, with his 93 kills, of course believes in his mission, and he is able to evoke the Vietnam jungle with some skill. yet there were times when the stories seemed to end too quickly. what happened to the Apache? where did the other soldiers end up in post-war life?

3/5 but to some degree missing the 4 only due to the plethora of other great titles acquired recently. supposedly `The` Nam sniper memoir, possibly even `The` sniper memoir

The Longest Day: The Classic Epic of D-Day

1959 "Classic Epic", as its subtitle goes, deserves its reputation as tightly-written, well-researched and accurate military non-fiction. from the Rangers at Pointe du Hoc to the 82nd All-American Airborne airdropping behind enemy lines, Ryan`s work is complete and detailed. WW2 historians probably enjoy pointing out that the entire D-Day Allied casualties was less than three days`s casualties in the Battle of Stalingrad (which raged for half a year), but, well, there was risk, there was planning, there was plenty of hard work. we cannot deny the Canadians their due.

1959 "Classic Epic", as its subtitle goes, deserves its reputation as tightly-written, well-researched and accurate military non-fiction. from the Rangers at Pointe du Hoc to the 82nd All-American Airborne airdropping behind enemy lines, Ryan`s work is complete and detailed. WW2 historians probably enjoy pointing out that the entire D-Day Allied casualties was less than three days`s casualties in the Battle of Stalingrad (which raged for half a year), but, well, there was risk, there was planning, there was plenty of hard work. we cannot deny the Canadians their due.ha... actually, statistically, D-Day was a Canadian invasion based on number of troops contributed versus population. thought I would throw that military arcana out there. the raid at Dieppe was also Canadian, I believe. guess I know more military trivia than I know what to do with. of course, statistically, the USA was the largest contributor of troops-- it`s just that the US has a much larger population than Canada.

anyway, 4/5 tightly written; detailed